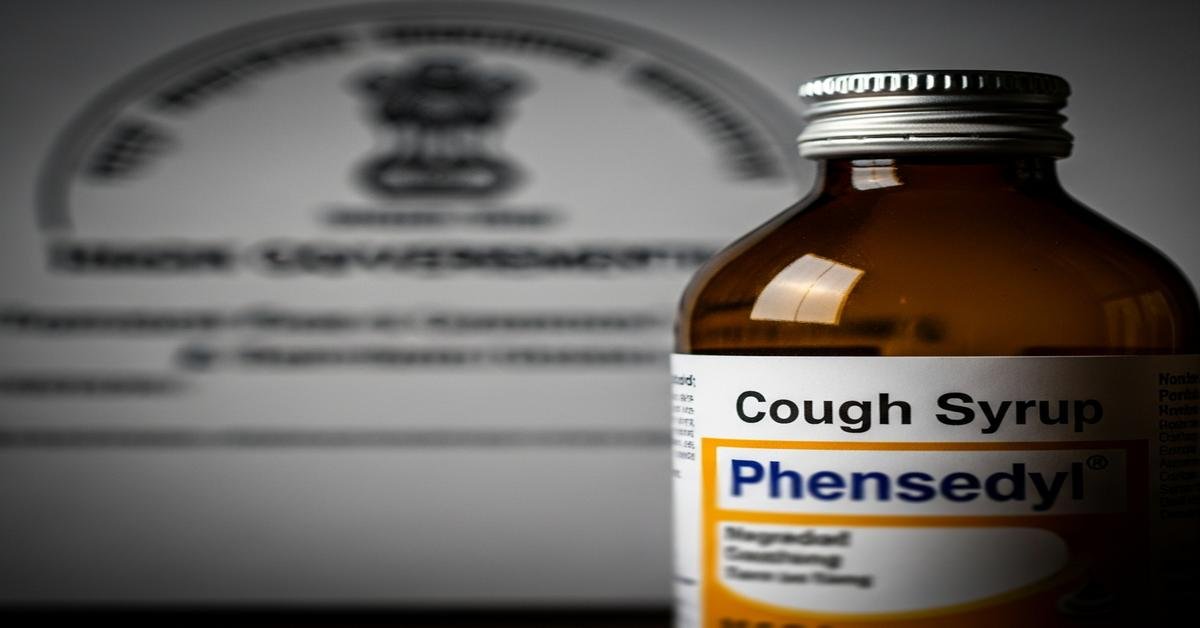

India’s decision to ban several fixed-dose combination (FDC) drugs, including popular cough syrups like Phensedyl, was not a sudden crackdown on household names. It was a long, technical argument about evidence, safety, and how medicines should be approved. This article explains what FDCs are, why the government acted, what the courts said, how industry responded, and what it means for patients and prescribers today.

What is an FDC and why do they exist?

An FDC is a single product with two or more active drugs in fixed proportions. Some FDCs are lifesaving. For example, fixed combinations for tuberculosis or HIV improve adherence and reduce resistance by ensuring patients take all required drugs together.

But many FDCs mix medicines without solid evidence that the fixed ratio is needed or even safe. When that happens, patients get extra side effects without extra benefit. Doses cannot be adjusted for each ingredient, and interactions become harder to predict. That is the core problem the Indian government tried to solve.

How FDCs proliferated in India

For years, thousands of FDCs entered the Indian market through state licensing, often without central approval or robust clinical data. This created a patchwork: some FDCs were widely sold for decades despite limited proof of safety, efficacy, or need. Doctors got used to them. Patients trusted the brand names. Meanwhile, regulators worried about irrational combinations and misuse.

Why cough syrups like Phensedyl were targeted

Many banned cough syrups combined an opioid antitussive (usually codeine) with an antihistamine (such as chlorpheniramine). These formulations were popular brands like Phensedyl and Corex.

The government’s concerns were specific:

- Abuse and dependence: Codeine is an opioid. In cough doses it can still cause euphoria in some users. These syrups were widely misused, and smuggling into neighboring countries became a law enforcement problem. When a medicine is easy to abuse, regulators demand stronger justification for its over-the-counter presence; many of these syrups were, in practice, easy to access.

- Questionable benefit in routine cough: Most acute coughs are caused by self-limiting viral infections. Opioids do not fix the cause. International guidance discourages codeine for children and does not recommend opioids for routine cough in adults because the benefit is modest and the risks—sedation, constipation, respiratory depression—are real.

- Irrational combinations: Many syrups bundled multiple ingredients with conflicting actions. An antitussive suppresses cough; an expectorant tries to thin mucus for easier coughing; adding a sedating antihistamine worsens drowsiness. This “kitchen sink” approach increases side effects without proving better outcomes.

- Dose inflexibility: In a fixed ratio, you cannot adjust codeine without also changing the antihistamine dose. That makes individualization impossible.

The legal and regulatory path to the ban

Starting 2013, an expert committee examined thousands of FDCs sold in India. In 2016, the government used powers under Section 26A of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act to prohibit the manufacture and sale of several hundred FDCs, including codeine–antihistamine cough syrups.

Manufacturers challenged the ban. Courts asked the government to re-examine the evidence using a transparent, scientific process. A new subcommittee reviewed data on safety, efficacy, international approvals, pharmacology, and whether each FDC had a therapeutic rationale.

In 2018, after this fresh review, the government banned 328 FDCs and restricted several more. In 2019, the Supreme Court largely upheld the ban. The legal bottom line: when the government is satisfied that a drug combination lacks therapeutic justification or poses risk of harm, it can prohibit it in the public interest.

What happened to the banned cough syrups?

Brands like Phensedyl and Corex were affected because their underlying combinations were banned. Some companies withdrew products. Others reintroduced them in new, permitted formulations without codeine (for example, using dextromethorphan with or without an antihistamine). The brand names sometimes stayed, but the ingredients changed. That is why reading the label—not just recognizing the brand—is essential.

Is the ban a blanket attack on cough medicines?

No. The ban targeted irrational combinations. Single-ingredient medicines, or rational two-drug combinations with evidence, remain available. Doctors can still prescribe codeine for specific patients with severe, refractory cough, but not as part of an unjustified fixed blend aimed at broad, routine use.

The evidence problem: why “long use” was not enough

Manufacturers argued that many FDCs had been used by millions over decades, implying safety. Regulators countered that widespread use does not prove effectiveness or safety without systematic evidence. Here’s why:

- Bias in routine use: Side effects are underreported; benefits are overestimated. Without trials or robust observational data, risks like sedation, falls, or misuse are easy to miss.

- Pharmacological reasoning matters: If two ingredients have opposing goals (suppressing cough versus aiding expectoration), the combination needs strong proof it helps more than it harms. Most banned FDCs lacked such proof.

- Global benchmarks: Many combinations were not approved in stringent regulatory jurisdictions. That does not automatically mean they are unsafe, but it raises the standard of proof needed to justify them.

Public health reasons beyond cough

The FDC cleanup went far beyond cough syrups. Many banned combinations involved painkillers, antibiotics, and steroids. The concerns included:

- Antimicrobial resistance: Irrational antibiotic FDCs can fuel resistance by exposing bacteria to suboptimal doses or unnecessary agents.

- Duplicate therapy: Two drugs with similar actions increase toxicity without better outcomes (for example, multiple NSAIDs together).

- Hidden risks: Extra ingredients bring extra interactions—especially dangerous for children, older adults, and people on multiple medicines.

What this means for patients

Check ingredients, not just brand names. The same brand may have changed its formulation after the ban. Look for the active ingredients and their strengths on the label. Know what each one does.

Avoid multi-symptom “cocktails.” For most coughs from colds, rest, fluids, and time are enough. If needed, use targeted treatments—such as a single-ingredient antitussive at night for dry cough or a saline nebulizer for congestion—rather than multi-ingredient syrups that sedate and complicate dosing.

Children need special caution. Sedating antihistamines and opioids are risky in kids. Always ask a pediatrician before giving cough medicines to children.

Watch for drowsiness and interactions. If a medicine contains an antihistamine or opioid, avoid alcohol and driving. Report unusual sleepiness, breathing difficulty, or confusion immediately.

What this means for prescribers and pharmacists

- Prescribe by molecule, not brand. Fix the objective (ease nocturnal dry cough, reduce bronchospasm, treat allergy) and choose targeted agents with clear evidence.

- Favor single-ingredient products. Combine only when there is a strong rationale and flexibility is not required. Keep doses adjustable.

- Counsel on non-drug measures. Hydration, humidification, smoking cessation, and treating reflux or asthma triggers often help more than sedating syrups.

- Screen for misuse risk. With any opioid, assess dependence risk, keep the dose and duration minimal, and document a clear indication.

The controversy: were there downsides to the ban?

Yes, and they are worth acknowledging.

- Disruption and confusion: Patients lost familiar products. Some physicians felt blindsided. Clear communication lagged enforcement.

- Uneven enforcement: Banned products lingered in some markets, while legitimate alternatives faced supply issues.

- Economic impact: Popular brands disappeared, affecting companies, retailers, and consumers who trusted them.

Even so, the core public health logic is strong: when combinations lack therapeutic justification or pose avoidable risks at scale, regulators must act. The long-term benefit is a cleaner market with fewer irrational options.

Did the ban solve the problem?

It helped, but vigilance is ongoing. The government clarified that new FDCs require central approval with evidence. Expert reviews continue. Companies reformulated many products into safer, rational versions. But habits change slowly. Prescribers and patients still need to look past brand loyalty and insist on justified combinations.

Practical takeaways

- For a routine cold and cough: Start with rest, fluids, and honey (for adults). If medicine is needed, pick the fewest ingredients at the lowest effective dose for the shortest time.

- Read labels every time: Do not assume the current bottle matches an older one with the same brand name.

- Be wary of syrups that promise “all-in-one” relief: More ingredients usually means more side effects, not more benefit.

- Use opioids only when clearly indicated: Severe, distressing, refractory cough may warrant them under medical supervision—not for routine viral coughs.

- Ask “what is the goal?” before choosing a drug: Dry cough at night, wheeze, allergic drip, or bacterial infection—each needs a different, targeted approach.

The bottom line

The FDC ban, including the removal of codeine–antihistamine cough syrups like Phensedyl’s earlier formulations, was driven by evidence gaps, safety concerns, and widespread misuse. Courts required the government to follow a rigorous process, and after fresh expert review, most bans stood. The controversy reflected a clash between habit and evidence. Going forward, India’s medicine market will be safer if prescribers favor rational therapies, patients read labels, and regulators keep demanding proof that combinations do more good than harm.

I am a Registered Pharmacist under the Pharmacy Act, 1948, and the founder of PharmacyFreak.com. I hold a Bachelor of Pharmacy degree from Rungta College of Pharmaceutical Science and Research. With a strong academic foundation and practical knowledge, I am committed to providing accurate, easy-to-understand content to support pharmacy students and professionals. My aim is to make complex pharmaceutical concepts accessible and useful for real-world application.

Mail- Sachin@pharmacyfreak.com